Publication 24 January 2023

The future of digital technologies governance

The 17th edition of the Internet Governance Forum was held a few weeks ago in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. On 14 October 2022, the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) Plenipotentiary Conference concluded. As the year draws to a close, the future of digital technologies governance is in tension. On 16 November 2022, the European Digital Services Act (DSA) came into force. The DSA places new responsibilities on platforms to limit the distribution of illegal or harmful content and products online, to strengthen the protection of minors, to provide users with more choices and to improve information. It comes on top of the numerous texts recently adopted or being developed at the European level to regulate digital practices, such as the revised Audiovisual Media Services Directive (known as the “AVMS Directive”), the NIS 2 Directive aimed at ensuring a common high level of cybersecurity throughout the Union, the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), the Digital Markets Act (DMA[5]), the proposed Artificial Intelligence Act (AI Act) and the European Commission’s recent proposal for a Regulation against online child sexual abuse (CSAM). This intense legislative activity at the European level is complemented by various initiatives in European Member States and at the global level. In France, these developments concern, for example, the fight against disinformation, terrorist content and online hatred, the supervision of access to pornographic content, the protection of child influencers, the regulation of the press and marketplaces, etc. The regulation of uses has become, in recent years, the most visible tool of digital governance.

However, in the field of digital technologies it is essential to take into account various levels of governance, to cover issues like uses, but also the infrastructure and networks on which telecommunications are based, the technologies that enable these exchanges, the standards and protocols that govern them, etc.

As regulation seems to be overtaking other dimensions lately, it seems appropriate to ask ourselves about the future of digital tech governance. What does “governance” mean, in terms of digital technologies? What should be the role and responsibilities of the various stakeholders involved in it (governments, private actors or civil society, for instance)? What place should users have in this governance? Given the substantial geopolitical dimensions of the subject, how can these respective roles be thought out to guarantee a digital world that is faithful to European values?

These issues were the subject of the French segment of the 2022 Internet Governance Forum (IGF) opening session. Co-hosted by Lucien Castex (Afnic) and Jessica Galissaire (Renaissance Numérique), this session brought together Maryse Artiguelong, Member of the National Bureau of the Ligue des droits de l’Homme (LDH) (the French League of Human Rights), Gilles Brégant, Director General of Agence nationale des fréquences (ANFR) (the French Frequencies Agency), Thomas Dautieu, Director of legal support at the French data protection authority (CNIL), Tawfik Jelassi, Assistant Director of UNESCO for Communication and Information, Benoît Loutrel, Member of the College of the French Regulatory Authority for Audiovisual and Digital Communication (Arcom) and Henri Verdier, French Ambassador for Digital Affairs.

Watch the debate

Understanding the concept of “Internet governance”

Internet governance, as defined at the 2005 World Summit on the Information Society (WSIS) in Tunis, is the “development and application by governments, the private sector, civil society and the technical community, in their respective roles, of shared principles, norms, rules, decision-making procedures, and activities that shape the evolution and use of the Internet” 1. This definition, although debated, lays out the foundations of the multi-stakeholder model. The place of citizens, or in other words Internet users, must be at the heart of the concerns, as put forward by Maryse Artiguelong. Digital technologies and the Internet overlap to a certain extent but not entirely, as observed by several speakers: the term “digital” refers to “all applications that use a binary language that classifies, sorts and distributes data. It encompasses interfaces, smartphones, tablets, computers, televisions, and the networks that carry the data. It covers tools, content and uses.”2 Therefore, Internet governance is only one of the components of the governance of digital technologies.

Distinguishing the different layers of digital technologies to understand their governance accurately

The speakers started with the observation that the public debate sometimes tends to mix the different layers of digital technologies3 and to encompass various levels of governance (although they all deal with various issues), within a single ill-defined whole.

According to Henri Verdier, this entails the risk of implementing ill-adapted regulation, by not grasping the issues “where they are”4, and even weakening existing balances that have proven their stability for several decades. The French ambassador for digital affairs recalls the need to distinguish between three layers: the “technical” layer, which includes, among other things, the cables and infrastructure that allow access to the Internet, “which is often overlooked and not given enough attention, despite its crucial role”; the “logical” layers, which refer to the Internet network as such and include protocols like TCP/IP5; and the “application” layer, which refers, among other things, to the Web, e-mail, the Internet of Things and social networks. “When we talk about digital governance, we go through all these layers”, he says, even though “these three layers raise issues that are certainly interconnected, but distinct”. Depending on the issues at stake, the relevant forums, the foundations of the legitimacy of the actors concerned, and the normative frameworks we refer to, are not necessarily the same. It is therefore essential to differentiate the different levels of governance, which all bear their own set of challenges.

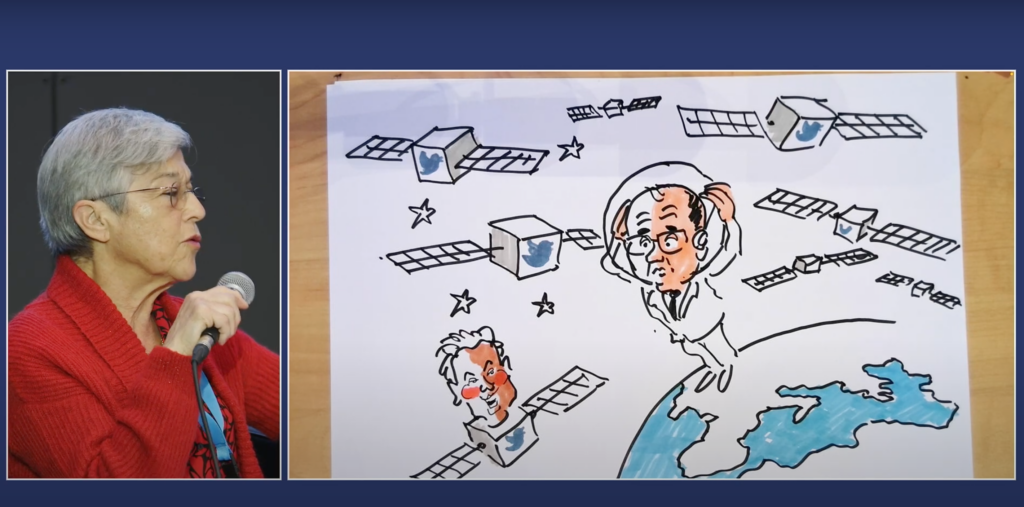

The first challenge identified by the speakers is the low priority given to the technical layer in discussions within multilateral digital governance bodies. One issue is, as Gilles Brégant points out, the radio frequencies used to connect to the Internet. According to the ANFR’s Director General, using satellite constellations to access the Internet will become mainstream in the years to come. There could be around 50,000 satellites in low orbit by 2028, i.e. 25 times more than today. Satellite constellations would thus represent the “third dimension of the Internet” after wired and wireless connections such as Wi-Fi. Because they are situated in space, satellite constellations allow for a much less intermediated Internet connection, limiting the possibilities of regulating access. Thus, their governance becomes more direct. This situation raises new questions, which must be anticipated. For Gilles Brégant, particular attention must be paid to the ownership of these constellations, whether they are state-owned (like the Guowang network developed by China) or privately owned (like Elon Musk’s Starlink).

Gilles Brégant

Director General of Agence nationale des fréquences (ANFR) (the French Frequencies Agency)

At the level of the logical layers, Henri Verdier observes that some key protocols, such as TCP/IP (which notably allows computers to exchange data on the Internet), are threatened by Chinese or Russian players who are carrying out projects for more centralised and supervised networks, like New IP or IPV6+. It is the European vision of a secure, free and open Internet that is endangered here.

Finally, concerning the application layer, although regulations are taking shape at the European level, issues relating to their full effectiveness still need to be overcome. Furthermore, although the Old Continent enjoys a certain form of leadership in this respect6, European voices remain too little present within key Internet governance bodies such as the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN) or the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF), regrets Henri Verdier. However, he said, we shouldn’t act as “sorcerer’s apprentices” and shouldn’t question this Internet governance, “which has been working for 50 years”. He also observed that time should be given to the numerous texts recently adopted at the European level to show their effects.

Henri Verdier

French Ambassador for Digital Affairs

Regulating digital uses: defending European values across borders

The European Union has positioned itself as a pioneer in regulating digital uses. By imposing rules and governance procedures, regulations limit uses that violate human rights and freedoms. In this respect, Tawfik Jelassi considers that the digital world is a “tool at the service of humanity, shaped by humanity, which conveys human rights, values and principles that we all share”. UNESCO defends this approach to cyberspace, which must be a vehicle for values, rights and fundamental freedoms that ensure respect for human rights. This approach is at the basis of the ROAM principles – according to which the Internet should be human Rights-based, Open, Accessible to all and nurtured by Multi-stakeholder participation – and of the dynamic coalition initiated on the occasion of the Internet Governance Forum in 2020. Thus, for the UNESCO Assistant Director for Communication and Information, the Internet must remain open and accessible to all. But it must also respect certain principles prescribed by the various legal frameworks in force to guarantee our rights. Hence the need to fight against hate speech, misinformation, disinformation, conspiracy theories, etc.8

Benoît Loutrel reminded us that the Internet pre-exists these regulations and that its borders are not the borders of the law. Consequently, regulators must collaborate at the European level “within networks”. This observation was shared by Thomas Dautieu, who notes a change introduced by the GDPR in this respect: “The European data protection authorities cooperated before the GDPR, but they now cooperate within the European Data Protection Board (EDPB), via a precise, demanding mechanism, which works well”. Benoît Loutrel adds that we must not stop at European borders. European regulators must strengthen ties between themselves and engage in a dialogue to improve the effectiveness of the regulations they have to enforce, but also to encourage the emergence of good practices on a global scale. In this respect, he observes that the mechanism put in place within the framework of the DSA should make it possible to go beyond the known paradigms: “Of course, we already had networks of audiovisual regulators. But we will move towards more teamwork within a more integrated network of regulators, with the European Commission at the centre when the very large platforms are concerned, and all the national regulators. […] The DSA will make it possible to merge all the initiatives undertaken at the national and at the EU level, to act truly collectively.” For instance, Arcom dialogues and collaborates in particular with the Office of Communications (Ofcom) in the United Kingdom and other Anglo-Saxon regulators within the framework of the World Economic Forum, as well as within the Network of French-speaking Media Regulators (REFRAM), which comprises 31 member institutions from Africa, North America and Europe. “Even though different jurisdictional plates coexist, what we are trying to obtain at the European Union level (a more virtuous behaviour of the big platforms) goes beyond the European Union”, said Benoît Loutrel.

Benoît Loutrel

Member of the College of the French Regulatory Authority for Audiovisual and Digital Communication (Arcom)

In terms of the influence of the European model for regulating digital uses, extraterritoriality emerged as a key factor in the discussions. For example, Thomas Dautieu emphasised that, in addition to its effects at the European level, the GDPR has had international repercussions for several reasons. “It is one of the first European regulations to apply even to companies located outside the European Union, even when they do not have an establishment in the European Union”, he said. Moreover, this regulation has enabled a movement of “data diplomacy” to emerge, he added: the GDPR is becoming a benchmark in terms of governance and personal data protection, which countries such as South Korea and Japan are gradually aligning themselves with.

Thomas Dautieu

Director of legal support at the French data protection authority (CNIL)

Putting the user at the centre of multi-stakeholder digital governance

The participants observed that a multi-stakeholder approach involving end-users is essential. In this respect, Maryse Artiguelong regretted that individual citizens are not more involved in this governance. Rather than being directly involved, she noted, their interests are most often defended by civil society organisations like the LDH. These actors provide an information and watchdog function (via appeals to the Conseil d’État (Council of State), participation in public consultations, or the filing of complaints with the CNIL). However, the LDH representative feels that public decision-makers do not sufficiently hear civil society and calls for greater involvement of civil society upstream of decision-making processes.

Maryse Artiguelong

Member of the National Bureau of the Ligue des droits de l'Homme (LDH) (the French League of Human Rights)

Several participants recommended, in particular, greater involvement of young people, who are, in their opinion, the first persons to be concerned. The LDH and CNIL representatives emphasised the importance of informing and promoting awareness around online rights8 from a very young age, so that as many citizens as possible can exercise these rights more directly in the future.

Tawfik Jelassi reaffirmed the need to establish and maintain a dialogue that is not only multi-stakeholder but also multilateral, to take into account the positions of all countries and not only Western ones. “UNESCO cooperates with all actors, including technology companies and platform operators, to facilitate a dialogue between its 193 member countries, civil society, NGOs, technology companies, academia and research, to identify principles and a global regulatory framework to ensure that information remains a public good and does not become a public ‘evil’ or a public risk”, he said. Reflecting on this point, Benoît Loutrel stressed that the regulators’ role is “to organise the participation of all” in the governance, and underlined that it is essential that digital platforms be part of the solution, and not just of the problems they may cause. He added that researchers’ access to platform data will be critical to collectively identifying solutions.

Tawfik Jelassi

Assistant Director of UNESCO for Communication and Information

Finally, according to Henri Verdier, the civil society in Europe is less vocal and less influential than in the United States. There are not enough researchers in the fields of human and social sciences on these subjects. Echoing this point, Benoît Loutrel identified the mobilisation of the general public as the main issue on which we must focus our efforts in the coming months: “Our society is entering the age of digital maturity. New frontiers are emerging. How do we reach the masses of citizens? The Internet is at the heart of everyone’s daily life, and we must involve everyone”, he said. Complementing these remarks, Gilles Brégant insisted on mobilising the diversity of actors involved as early as possible: “We must involve the various actors further upstream, to anticipate and avoid constantly having to fight yesterday’s battles. This approach implies having several ‘layers’ of actors (actors who anticipate, actors who consolidate, actors who implement), for a more solid governance, which comes in time.”

1 World Summit on the Information Society, Report from the Working Group on Internet Governance, WSIS-II/PC-3/DOC/5], 18 July 2005.

2 Translated from Dubasque, D. (2019), Comprendre et maîtriser les excès de la société numérique, Presses de l’EHESP, p. 17.

3 The governance of deep infrastructures, technical norms and standards, the regulation of private players, the ethics of artificial intelligence…

4 “There should be a basic axiom: one should try, as much as possible, to deal with the problems of the high layers in the high layers and not always look for solutions in the lower layers.”

5 The Transmission Control Protocol/Internet Protocol (or TCP/IP) combines the TCP and IP protocols. It is a protocol suite associated with the Internet domain, which facilitates the transfer of data. See also Cerf, V. (2022), “Evolving the Internet”. Telecom, No. 204.

6 General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), Digital Services Act (DSA), Digital Markets Act (DMA), AI Act, Data Act, Christchurch Call to Action to eliminate terrorist and violent extremist content online, Paris Call for Trust and Security in Cyberspace…

7 From 21 to 23 February 2023, an international conference on the regulation of digital platforms will be held at UNESCO’s headquarters to address these issues. Learn more: https://www.unesco.org/en/internet-conference

8 For example, the right to data portability, guaranteed by the GDPR.