Publication 16 June 2020

Facial recognition: Embodying European values

The technical maturity of facial recognition technologies paves the way for their deployment

Despite significant technological progress, FRTs remain imperfect and highly sensible devices. The processing of biometric data is long from being trivial, and the risk of violating our fundamental rights and liberties deserves special attention. The systems on which these technologies rely can indeed fall victim to serious security breaches, not to mention the algorithmic biases they’re susceptible to, which can provoke cases of racist, sexist or agist discrimination. Beyond these technical imperfections, certain errors may be the result of human intervention when interpreting the results from these technologies, which rely on probability.

Nevertheless, FRTs bring together an extremely diverse pool of applications. Not all uses (public or private, consensual or unknown to individuals, in real time or deferred, etc. ) bear the same sensibility and risk factors. These cases of more or less sensitive applications and experimentation are multiplying, including in several EU Member States. It is therefore necessary to ask whether the legal framework surrounding them is sufficient to prevent the use of facial recognition technologies that could jeopardise our fundamental rights.

Examples of fundamental rights likely to be affected by the use of facial recognition technologies

| Fundamental rights or freedoms | Impact of facial recognition technologies |

| Human dignity | Facial recognition technologies, especially when used in real-time, can be seen as surveillance technologies that are intrusive enough on people’s lives to affect their ability to lead a dignified life. |

| Non-discrimination | Discrimination may occur in the design (conscious or unconscious) of the algorithm itself (through the introduction of bias) or as a result of the implementation, by those who decide what action to take based on the result of the algorithm. |

| Freedom of expression, association and assembly | The use of facial recognition technologies through video cameras installed in public space can deter people from expressing themselves freely, encourage them to change their behaviour or revert to presenting them as part of a group of individuals. Some people may not want to gather in public spaces for fear of facial recognition technologies. This may also violate the freedom to remain anonymous. |

| Right to a fair trial | This right rests first and foremost on people’s right to be informed. Thus, any lack of transparency could undermine this right70. In addition, public authorities must put in place procedures to enable the persons concerned to bring challenges and complaints. For example, individuals should be able to object to their inclusion in a matching database or claim compensation for damage due to misinterpretation of the results of facial recognition technologies. |

| Right to good administration | It refers to the concept of explicability and is based on a principle of transparency which implies that individuals may request to know the reasons why a decision has been taken against them. With regard to facial recognition technologies, this would mean that the administration or the police would have to be able to explain to a person the reasons why he or she has been arrested on the basis of the results of a facial recognition technology. |

| Right to education | A student who is denied access to a school in a region that has mandated access through facial recognition technologies, and does not offer any other access alternatives, may invoke his or her right to education. |

| Source : Agence des droits fondamentaux de l’Union européenne (2019), “Facial recognition technology: fundamental rights considerations in the context of law enforcement”. | |

An inconsistent and inefficient application of the legal framework

Today, no rules specifically frame the deployment of facial recognition technologies at the European level. The Charter of Fundamental Rights, the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and the Law Enforcement Directive constitute however a series of safeguards intended to guarantee the protection of the fundamental rights of citizens. In compliance with this framework, the processing of biometric data is, save for some exceptions, prohibited in the European Union (EU). National provisions, such as the Loi informatique et Libertés in France or the regulation on video-protection, complete this legal framework. Thus, the deployment of FRTs is not carried out in a legal vacuum in the EU.

Nevertheless, this legal framework suffers from weaknesses in its application, making it inefficient. It is imperative to remedy it. On the one hand, European regulations are applied in a variable manner from one Member State to another. In addition, national regulatory authorities have disparate and insufficient human and financial resources to devote to proper implementation. On the other hand, the oversight over the respect of our fundamental rights and liberties is a complex exercise that generally happens ex post, through jurisprudence – in other words, in reaction to a specific experimentation or deployment. As such, the compatibility of the applications of facial recognition with fundamental rights and liberties is not guaranteed ex ante.

If our aim is to ensure that FRTs are deployed in accordance with European values – that is to say in compliance with the principles of the rule of law and democracy –, then we cannot be satisfied with this current situation. At a time when more and more facial recognition technologies are being deployed, there is an urgent need for the European Union to address these issues and for Member States to agree on a robust system to guarantee our rights.

Towards a European standardisation system guaranteeing fundamental rights and freedoms

For the time being, the facial recognition technology standards applied in the EU are principally those of the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), an American government agency. Therefore, there is an opportunity for Europe to emancipate from American predominance and to decide on its own rules, considering in addition that these standards only take into account the technical performance of these technologies (without consideration of potential impacts on our rights and liberties).

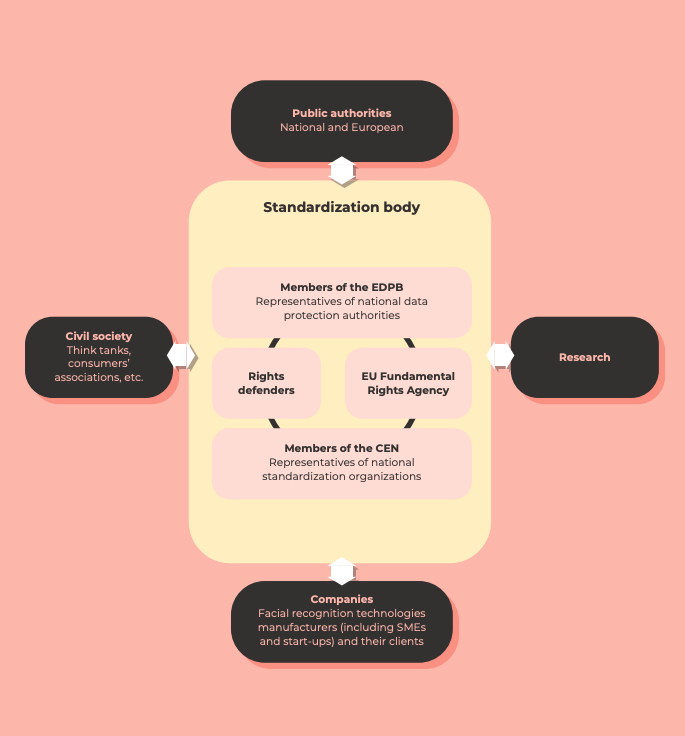

In order to establish its digital sovereignty and protect the fundamental rights and freedoms of its citizens, the EU must then define its own standards and integrate legal dimensions into them. The adoption of these standards must be achieved by imposing them in European, national and local public markets, including for experimentation. This would, on the one hand, encourage their adoption and, on the other, provide a strong framework for public surveillance. To define these standards, the EU must rely on a multi-stakeholder governance body, bringing together expertise in the fields of standardisation and fundamental rights, including personal data protection, and, more generally, rights defence.

The potential structure of a European standardisation body for FRTs

GROUPE DE TRAVAIL

Groupe de travail

-

Sarah Boiteux

Google France

-

Hector de Rivoire

Microsoft France

-

Etienne Drouard

Hogan Lovells

-

Valérie Fernandez

Telecom Paris

-

Léo Laugier

Institut Polytechnique de Paris

-

Guillaume Morat

Pinsent Masons

-

Delphine Pouponneau

Orange

-

Marine Pouyat

W Talents

-

Philippe Régnard

La Poste

-

Annabelle Richard

Pinsent Masons

-

Thierry Taboy

Orange

-

Amal Taleb

SAP

-

Valérie Tiacoh

Orange

-

Publication 9 June 2021

Regulation of facial recognition technologies