News 30 November 2022

Decentralised social networks: towards an ethical Web3?

On 28 October 2022, American billionaire Elon Musk announced he had bought the social network Twitter for 44 billion dollars. After several months of twists and turns, this operation raises fears of major changes in the content moderation rules on the platform – whose policy in this area is also regularly denounced as ineffective: Elon Musk has presented himself as the guardian of an extended freedom of speech, pledging to “free the bird“. The effects were not long in coming: he fired Twitter’s CEO Parag Agrawal, Head of Legal Affairs Vijaya Gadde and General Counsel Sean Edgett upon arrival, and severely curtailed the moderation capabilities of the Trust and Safety team, which is responsible for combating misinformation, hateful content and harassment. This reversal highlights the capacity of social networks to define and change the ways in which their users express themselves and interact with each other. In the case of Twitter, its new owner is, within the limits of existing legal frameworks1, in a position to decide alone (or almost alone) the rules2 to which its 436 million active users will be subjected.

This takeover also sheds light on the business models of “traditional” social networks, whose market is concentrated in the hands of a small number of players, and which are based on a centralised architecture articulated around servers which they themselves own. Social networks such as Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, TikTok or Twitter belong to companies whose business model is based on the combination of the direct network effects of communication networks with the connection to market places. The centralisation of users’ data by these platforms makes it possible to create audiences and maximise network effects, which reinforces the power of the model for advertisers. The data produced by users is thus the basis of this economic model. On the one hand, it is used to feed recommendation algorithms, which make it possible to propose personalised content designed to capture the attention of users, and encourage them to spend more time on the platform. On the other hand, it can be reused by third-party companies for advertising targeting purposes. As the Cambridge Analytica scandal has shown, these practices can go as far as political targeting, and thus undermine the proper expression of democracy. In addition, several studies have shown that the dissemination of certain content, such as conspiracy theories, was reinforced by the recommendation algorithms of certain social networks. Thus, the phenomenon of echo chambers, which contribute to polarising debates and even threaten the stability of democratic institutions, is often denounced. The harmfulness of algorithms, which shape the way content is consumed on social networks and which affect both the quality of democratic public debate and the mental health of users, is also denounced. The Facebook files have highlighted some of these effects and various studies (here and here) point in the same direction. These problems are the result of the models chosen by the main social networks, which are based on the attention economy. However, several scientific studies have found that the effects of filter bubbles3, echo chambers and cognitive biases induced by the algorithms are overestimated.

States have nevertheless taken up the issue of the regulation of large digital platforms in the hope of limiting the negative effects that certain phenomena or certain content (cyber-bullying, disinformation, targeting, exposure to illegal or harmful content) can have on individuals and the exercise of their rights and freedoms. However, these efforts may not be sufficient and, at the very least, take some time to have an effect. In parallel, an alternative model which offers another form of online expression and interaction has emerged: decentralised social networks. Offering similar functionalities and services to those of the major social networks, they differ in terms of architecture by their open source nature and the absence of a centralised proprietary entity. These networks belong to the community of users, who decide which uses are permitted. On these networks, users own their personal data. Numerous projects aimed at encouraging the development of decentralised social networks have emerged in recent years, particularly as a result of the hype surrounding blockchain technology. These projects are all the more popular as social networks have entered a period of reconfiguration and are forced to rethink their economic and governance models. Facebook, for example, has set up an Oversight Board, while Twitter is considering setting up a “Content Moderation Board“. Furthermore, the modes of interaction on these centralised platforms are being questioned and are challenging our digital sociability.

Elon Musk’s takeover of Twitter, which resulted in almost a million users leaving the network in five days, has put these decentralised alternatives back at the heart of the debate. It offers an opportunity to question their potential and their limits. Do decentralised social networks offer a credible alternative model for giving users back control over their personal data and their uses? Can they breathe new life into our digital interactions?

The ambition of decentralised social networks: changing the “rules of the game”

To understand how decentralised social networks work and what differentiates them from others, it is necessary to make a distinction between the protocol layer and the application layer: these are two sides of a same coin. Protocols refer to the architecture of the network: they make it possible to build a decentralised architecture. They are then used by other actors to create applications or platforms offering their own services, functionalities and conditions of use. The architecture is therefore distinct from the so-called application part, which is built upon it.

A shared resource, focusing on the individual control of personal data

Decentralised social networks are networks which have a de facto decentralised architecture: the information exchanged does not pass through a single, central entity that obtains sometimes very extensive usage rights. In this respect, they differ from centralised social networks, which are more commonly used, such as Facebook, LinkedIn or TikTok. The decentralised architecture is therefore considered an exception. However, nothing predetermined social networks to favour this centralised approach. The Internet is by nature a decentralised network, and the Web was, at its inception, the vehicle of a strong culture of decentralisation.

At the application level, the emergence of Web2 in the 2000s allowed the creation of online social exchange platforms: social networks. These quickly developed as services offered by companies whose business model is based on capturing market share and monetising users’ personal data. These companies (LinkedIn, Meta, TikTok, Twitter, etc.) centralise their users’ data (publications, “likes”, comments, followed accounts, subscribers, etc.) on their servers, obtain the rights to use them, and can therefore, thanks to this right of use, offer personalised content to users or advertising targeting services to third parties. In addition, these companies have significant control over the social network: they define the rules via their “Terms and Conditions” or “Rules of the Community” and can exercise censorship over the content published and over users via moderation policies and account suspensions4. The users do not, in fact, have any decision power over these rules5. This aspect has been denounced several times by Renaissance Numérique and we recommend, in this respect, that users be more involved in the governance bodies of digital platforms.

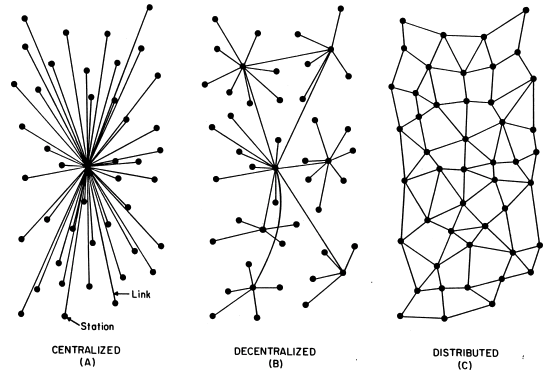

Decentralised social networks, on the other hand, are not subject to the power of a single actor who holds the information that transits through them and decides what can be said. Their architecture is such that several independent centres (also called “servers” or “instances”) operate the network. Decentralisation can even be total, making each actor in the network an independent “centre” so that there is, in fact, no centre at all. Decentralised networks can take two forms: they can be either federated or distributed6. This distinction is essential for understanding how they work and the development perspectives offered in this respect by Web3.

Federated social networks are based on a federation of servers. Users gather around these servers called “instances”, each managed by different entities. This model has the advantage of giving users the choice of the instance on which they want to interact (and thus, with whom and how) and to choose, as a consequence, who has access to their data and metadata. This is the case on Mastodon for example. Distributed social networks, on the other hand, do not have instances around which groups of users gather. There are no federations of servers, each user being its own server: the user is said to operate its own “node”. A distributed network is thus entirely decentralised, whereas a federated network is based on a multi-centralisation operated by a multiplicity of actors who are independent from each other. The figure below illustrates this distinction at the infrastructure level (the “Decentralized” representation should be understood as the representation of federated networks (see6)).

Schéma 1 – Architecture des réseaux sociaux centralisés, fédérés et distribués

Source : Paul Baran, “On Distributed Communication Networks”, 1964

| What is Web3 ?

Web3 is presented as the next Web generation which, based on blockchain technology, would be inherently decentralised and controlled by users rather than by a small number of companies who, because of their dominant position, dictate the “rules of the game”. The term was defined in 2014 by Gavin Wood, creator of Polkadot and co-founder of Ethereum, to designate “a decentralised online ecosystem based on the blockchain”7. The French Data Protection Authority, CNIL, defines blockchain as “a technology for storing and transmitting information” that “operates without a control body”. Via this technology, users can exchange information and assets securely, without going through an intermediary. Every transaction or exchange made since the creation of the blockchain is stored in the chain’s database, and a copy of the database is hosted by a multiplicity of nodes to which all users have access. The information exchanged is grouped into “blocks” and verified by a so-called “consensus” algorithm before being added to the existing chain. Each block addition is loaded simultaneously on all copies of the database held by the different nodes. The information and exchanges are thus secured by end-to-end encryption. Jean-Paul Delahaye’s analogy, which compares blockchains to “a very large notebook, which anyone can read openly and for free, on which anyone can write but which is impossible to erase and which is indestructible”, is particularly illustrative. |

Blockchain technology, as the cornerstone of Web3, offers the possibility of retrieving and securing the ownership of personal data via an independent storage solution. By relying on this technology, social networks have the possibility of decentralising social graphs which, in centralised networks, are owned by the network operators and not by the users. A social graph is the representation model of all the relationships and interactions of an individual on a social network: their friends, subscribers or contacts, their “likes”, their comments or their publications. They are at the heart of the economic model of centralised social networks. In the absence of portability and interoperability, they imply a significant opportunity cost8 for individuals willing to leave a social network platform. The social graphs currently held by the centralised networks thus play a key role in capturing their audience.

Revolutionary idea, pipe dream or creation of a lawless space?

Decentralised social networks, by putting users and their consent for data sharing at the core of their architecture, present themselves as a solution to end the control exercised by large platforms over our social graphs and online interactions.

Federated social networks, whose architecture is based on a multiplicity of independent bodies, function as a common that is self-managed and financed by the community of users. They do not allow for the centralised capture of personal data, nor their exploitation for commercial purposes. They are generally open source projects on which, at the application level, instances can be freely created. These instances are free to define their own rules (particularly with regard to content moderation, which also have negative effects), and manage their own operating costs. Each user, by creating a profile, chooses the instance he or she wishes to join9, i.e. indirectly, the rules of interaction and data collection to which he or she agrees.

Distributed social networks, on the other hand, ensure ownership of personal data through the individual control of social graphs. Users’ consent is brought to the fore: they decide who has access to their social graph, under what conditions, and can revoke this consent at any time. In addition, distributed networks open the possibility for users to receive an economic benefit from authorising access to their data. Finally, the storage of social graphs

on a blockchain could potentially enable data portability and interoperability at the application level. On the one hand, it is about being able to move from one platform to another, by forwarding one’s social graph, i.e. by keeping one’s contacts or conversations. On the other hand, it is about being able to interact with a person in your social graph, even if you do not use the same application or social network (provided that these two applications or networks have been designed to allow for the exchange to be readable).

However, decentralised social networks are not yet fully operational models.

Federated networks, although partially decentralised, have limitations: the multiplicity of instances does not put an end to the logic of having a centre. Each instance is led by an individual or organisation that decides upon the applicable rules within the community. In addition, the technical knowledge required to set up an instance and the costs involved in running them are obstacles that do not allow just anyone to set up their own. In fact, the largest instances are owned by associations or non-profit organisations, such as Framasoft, which hosts Framapiaf, or La Quadrature du Net, which hosts the Mamot server on Mastodon. In addition, the possibilities of interaction between members of different instances are sometimes limited by their administrators.

Distributed networks would make it possible to go further and offer a solution that is detached from any centre-based logic. However, although projects are underway, no technical solution is fully operational and deployable on a large scale at the moment. While some protocols are relatively mature (Lens, DeSo or DSNP, for example), an application ecosystem that would allow for a “general public” deployment of distributed social networks is still lacking. This raises technical questions, particularly concerning the interoperability required to make social graphs communicate with each other. Questions also remain in terms of user experience: in concrete terms, how to ensure smooth and efficient consent management (to access one’s graph and data)? Can the overall experience be comparable in terms of quality and fluidity to that offered by the major “traditional” social networks? The limited success of Mastodon10, which has been mostly adopted by versed users, suggests that user experience remains the main limitation to overcome for mass adoption and migration.

Furthermore, at the application level, the absence of central control and the definition of rules by users or community administrators can lead to abuses in terms of moderation. We could for instance observe the emergence of instances or platforms dedicated to hatred towards minorities, cyber-harassment, as well as to the expression of racist, anti-Semitic, sexist or conspiracy-related content. This relative laxity could also lead to the instrumentalisation of these networks by terrorist or extreme groups, or any other actor likely to engage in illicit or harmful activities.

Decentralised social networks and concrete applications: the unfulfilled challenge of an ethical Web

Projects under development and future perspectives

Several decentralised social networks’ projects have been developed over the past decade, both federated and, more recently, distributed.

The two most popular federated social networks are Mastodon11 and diaspora*12. Mastodon, created in 2016, is a “self-hosted, free and decentralised social network and microblog software”. Referred to as the “decentralised Twitter”, it allows users to exchange text, images and content on various independent and autonomously administered servers. Upon registration, users choose which of the 3,300 or so servers they wish to join. Alternatively, they can create their own server (although this requires significant technical skills). In practice, the majority of users join pre-existing ones, which may raise questions about the decentralisation model: a dependence is created on the administrator, who may adopt an ideological approach. Moreover, it can be observed that users tend to group together within the largest servers for the sake of convenience. However, no central authority can intervene in the event of a dispute with an administrator. As far as funding is concerned, each body is responsible for raising the funds necessary for its functioning, which is mostly done through crowdfunding. The takeover of Twitter by Elon Musk has recently increased the visibility of Mastodon, which has surpassed one million monthly active users (with almost half a million new users in a few days).

diaspora*, on the other hand, is an application developed in 2010 through participatory funding. It presents itself as an alternative to Facebook, and offers similar functionalities. A system of instances called “pods” allows the network to function. A governance model of its own has also been set up with the creation of the diaspora* foundation which allows the community to choose its own rules of governance. However, diaspora* has been the subject of controversy due to the weakness of its moderation rules: several hundreds of jihadists have joined various pods on which Islamic State propaganda has been shared. While the vast majority of the administrators concerned have chosen to remove this illegal content, there is no guarantee that no pod passing on Islamist propaganda exists.

With regard to decentralised social networks based on blockchain, current developments are mainly taking place at the protocol level. Blockchains offer an independent, secure and decentralised storage solution. Thus, several innovations have chosen to focus on the decentralisation of social graphs, by storing them independently on a blockchain. This decentralisation gives users back ownership of their social graph and allows them to decide to whom and how they give access to the data it contains.

The Lens and DeSo protocols are two such examples. Lens is based on the decentralisation of social graphs stored on blockchains. DeSo, on the other hand, is a proper blockchain allowing the decentralisation of social graphs, among other features. Both are open source protocols but have differences, especially in their business model13. At the application layer, social networks could be created on the basis of these protocols. An ecosystem of applications is also emerging: DeSo has an ecosystem of around one hundred applications and the Lens protocol is used by a smaller number of applications, including social networking apps such as Lenster. For the most part, these applications are currently in their beta phase and are not accessible on the iOS and Android application stores. Their use is therefore mainly reserved for a very restricted, informed and initiated public.

Another protocol enabling the decentralisation of social graphs is under development: the Decentralized Social Network Protocol (DSNP) developed by Project Liberty. This is an open source protocol that “aims to give users back control of their personal data and empower users to directly benefit from the economic value of their personal data.” 14 The DSNP is presented as a public good belonging to the community15, which is not intended to be commercialised. Indeed, its model does not rely on tokens16 at the protocol layer, unlike other protocols such as DeSo. However, this would not prevent a token-based model from emerging at the application level.

The DSNP will be adopted for the first time by MeWe, which has announced its intention to integrate it into its architecture. MeWe, a social network created in 2012, stands out for its strong commitment to privacy and user control of personal data17. The network now has 20 million users. It has particularly gained popularity in Hong Kong in 2019 and 2020 in response to fears of censorship on Facebook in the context of widespread public protests. However, MeWe is not exempt from criticism. The network has been accused of being a favoured platform for US ultra-conservatives and conspiracists because of its weak moderation rules. This raises concerns about the high degree of freedom allowed by some alternative social networks, including decentralised networks.

This first application also raises several questions, particularly about technical-practical aspects and user experience. It will probably allow to clarify both the possibilities offered by the decentralisation of social graphs on blockchains, and the limits of this alternative. If the transition to DSNP is successful, MeWe would become the largest decentralised social network existing today18.

Models that are still embryonic, and reinforce the need to rethink governance

Decentralised social networks hold great potential for ethical digital services that respect individual freedoms. However, depending on the services developed on the application layer, they may also accentuate existing problems of online hate and informational disorders, and may not lead to greater respect of privacy. As we have seen, these problems, which are essentially rooted in the application layer, cannot be solved by acting at the protocol level alone.

Lawrence Lessig’s initial premise was that “Code is Law“19, or in other words, that the way a computer code is written helps to regulate cyberspace by determining values, guaranteeing or not freedoms and allowing or not (and to a varied extent) respect for privacy. Based on this observation, Lessig called upon public decision-makers and civil society to make their voices heard and not to let developers alone choose the rules that define the functioning of cyberspace. However, research has shown that it is inaccurate to blame technology and the structure of protocols or social networks for all the problems we see online such as the polarisation of public debate20. In this respect, we should not fall into a technological overdeterminism. Social networks are above all places where the norms observed in the real world are reproduced. Thus, certain decentralised social networks could well encourage abuses, particularly because of the difficulties of moderation. One can imagine that some of them become fragmented spaces, where harassment, hateful, violent or racist comments could spread with greater ease than on centralised networks. Although the centralised architecture has a significant impact on the virality of content, the observed problems are more related to the models of governance, which do not, for the moment, include users. In this respect, decentralised social networks offer some opportunities. However, they are only building a road. The circulation conditions will depend on those who will use it.

In this respect, Project Liberty 21 has, for example, chosen to adopt a multidimensional and multi-stakeholder approach aimed at supporting the development of “ethical”22 innovations. In parallel with the development of the DSNP, this project is engaging in reflections on the governance of the Web and emerging technologies within the McCourt Institute23. Through the Unfinished network, it promotes dialogue with civil society, with the objective to place the latter at the heart of reflections on governance of the Web and Web3. The project, which is not only a technological project24, aims to anticipate future potentially problematic practices likely to emerge with the development of Web3, and to propose solutions to limit them.

Despite these developments, many questions about the potential application uses and user experience on a distributed social network remain unanswered for the moment. What will the interfaces look like? What will be the concrete changes for users, especially in terms of consent to data processing? Will they receive constant requests for consent? Will it be automated? Can consent be sectorised by category of use? Will new intermediaries appear to assist users and companies in managing consent? How will we be able to access and modify our social graph?

The decentralised social networks of Web3 also call for a redefinition of social networks’ economic models. These can no longer be based on the monetisation of users’ data. While many of the current projects tend to favour a system of tokens, other perspectives can be considered, such as paying for the access to the social network or to some of its functions. MeWe, for instance, is a free service. However, some of the additional features are subject to a fee, which ensures the financing of the social network. While this may not seem a viable option at first glance, the parallel with some streaming services, such as Netflix, is interesting: users have agreed to pay for a service that was previously available for free (albeit illegally), in exchange for a simpler, better and more secure access. Social networks could follow a similar trend, and move away from participatory financing logics (Mastodon, diaspora*) in order to strengthen their sustainability. The services and economic models thus remain to be imagined.

Furthermore, the inflection point we are experiencing is an opportunity to question the nature of the interactions we have on social networks, which itself stems from the design of their interfaces. These considerations are independent from the architecture of social networks (centralised or decentralised) and raise questions about the project of digital sociability that we wish to pursue. Web3, by making it possible to use smart contract systems to reward and encourage participation in governance25 or to encourage “good” and sanction “bad” behaviour online, opens the way to the commodification of public debate and the introduction of a market mechanism to regulate social actions. Confronted with the need to reinvent themselves, some dominant platforms could be tempted to rely on integrated purchases as a new source of revenue, and thus become hybrid objects, between a place of socialisation and a marketplace. Are these projects desirable? The debate is open and everyone, from those working on the development of Web3 technologies, to users, civil society, and the major current platforms, must take part in it. The future of our digital sociability depends on it.

1 For example, in Europe, the Digital Services Act (DSA), which will, among other things, impose obligations upon platforms with regard to the fight against the distribution of illegal or harmful content or illegal products.

2 The introduction of a “Twitter blue” subscription to be allowed to have a certified account on Twitter, for example, or the reactivation of suspended accounts such as those of Donald Trump or Kanye West.

3 See Hosseinmardi et al. (2021), “Examining the consumption of radical content on YouTube”, PNAS, Vol. 118 | No. 32; and Jürgens, P., Starck, B. (2022), “Mapping Exposure Diversity: The Divergent Effects of Algorithmic Curation on News Consumption”, Journal of Communication, Volume 72, Issue 3, June 2022, pages 322-344.

4 Platforms are obliged by numerous legal texts to exercise this moderation, particularly with regard to racist, negationist, terrorist or child pornography content. However, moderation can also be the result of the platform’s choices, particularly with regard to nudity (see the case of Instagram on this subject).

5 This has been denounced by Renaissance Numérique, which proposes to integrate users (or user representatives) into the governing bodies of large platforms, since they contribute greatly to the creation of value on these platforms. See Renaissance Numérique (2020), Digital platforms: for a real-time and collaborative regulation, 9 pp.

6 Narayanan, A., Toubiana, V., Barocas, S., Nissenbaum, H. and Boneh, D. (2012), “A Critical Look at Decentralized Personal Data Architectures”. We choose this typology rather than that of Paul Baran (often taken as a reference) which distinguishes between centralised, decentralised and distributed networks. For the sake of understanding and accuracy of the analysis, we consider “decentralised social networks” as an umbrella term including federated and distributed networks, and not as a separate category. In our analysis, “federated networks” thus correspond to what Paul Baran called “decentralised networks”.

7 “What Is Web3, Anyway?”, Wired, 3 December 2021.

8 Renaissance Numérique (2015), Platforms and competitive dynamics, 29 pp.

9 This choice may be very important in the case of networks such as Mastodon, where certain servers have a strong identity, and where very different rules apply regarding the free expression of personal opinions (ranging from a maximum to a more restrictive conception of freedom of speech).

10 Mastodon has just passed one million monthly active users compared to Twitter’s more than 326 million.

11 Free, open source and decentralised social network based on the ActivityPub protocol. In October 2022, Mastodon had more than 4,500,000 users and over 4,000 servers.

12 Free, open source and decentralised social network based on its own eponymous protocol. As of October 2022, diaspora* had over 730,000 users and 150 pods. The most active pod is diaspora-fr.org with nearly 40,000 users. Framasphere, owned by the Framasoft Foundation, was one of the main pods before it was closed in 2021 and users were redirected to diaspora-fr.org.

13 The DeSo protocol, for example, is based on a token exchange model for each publication, user tag or like action: this action has a cost and is paid for via tokens. A smart-contract system encourages users to interact on the network by redistributing 25% of the tokens spent.

14 See the Project Liberty website : https://www.projectliberty.io/

15 The code, which is itself built using other open source standards such as ActivityPub or Decentralized Identifier Specification, is open and a discussion forum is available to all.

16 A token is a digital asset circulated and exchangeable on a blockchain representing a right, value or power within a network. It can be a means of payment, a right of use or a copyright.

17 The platform has defined a “Privacy Rights Charter” in which it undertakes, among other things, never to sell or use users’ data for content recommendation purposes.

18 20 million users compared to 6.5 million for Mastodon.

19 Lessig, L., “Code is Law – On Liberty in Cyberspace”, Harvard Magazine, January 2000.

20 “How Harmful is social media”, The New Yorker, 3 June 2022.

21 A non-profit organisation based on the McCourt Institute and on Unfinished, a network of experts, policy makers, activists, academics and citizens committed to the protection of individual freedoms online.

22 Notion to be understood in a broad sense: innovations that respect individual rights and freedoms.

23 Research institute and networking place for experts and public decision-makers, launched in partnership with Georgetown University in Washington and Sciences Po Paris.

24 “It is not a tech project, it is a democracy project”, insists Frank McCourt, the project founder.

25 See Bueno de Mesquita, E., and Hall, A. (2022), “Paying people to participate in Governance”, a16z Crypto.

-

News 10 January 2023

-

Publication 3 July 2020

Moderating our (dis)content: renewing the regulatory approach